See the Safari; Camp Jabulani in Hoedspruit

August 17, 2018

3 Must-See International Jazz Festivals

August 22, 2018These days you can find odes to soul food on any fancy, white table cloth restaurant. Fried chicken, collard greens and offal (read: oxtails and chitterlings), once shunned in high society, are now considered du jour even in the poshest places. In the past decade, soul food has found mass appeal, just as many aspects of our background have resurfaced in popular culture. But that newfound appreciation often comes without regard for the history. In the first segment of our three-part interview, Dr. Frederick Douglass Opie, professor of History & Foodways at Babson College Southern food and Civil Rights, breaks down the origins of soul food.

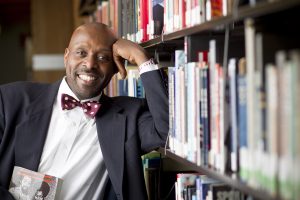

Dr. Frederick Douglass Opie

Q: Soul food as we know it today has a bad rap for being high in cholesterol and sugar and low in nutrients? But what were the healthy roots of soul food?

A: Well, I think the healthy roots of soul food if you take it back to our ancestors in West and Central Africa, we came from a culinary culture that is rich in green leafy vegetables and tubers, things like yams, all kinds of legumes and a lot of fish. And the consumption of red meat whether beef or pork were on very rare or special occasions. So that is the root of where we come from. A lot of that food was high in vitamins and minerals. But that has certainly changed when our ancestors were brought into captivity during the Atlantic Slave Trade here and living a life of deprivation, in which a lot of the healthy parts stayed in and a lot of the unhealthy parts crept in.

Q: What specific foods and traditions came from our African roots?

A: The enslaved people when they came over, they came over in ships that made sure those ships were stocked with the most basic staples of the people of African descent in order to keep that investment alive. I think it is important for people to understand that context, so even on the ships that enslaved people traveled on, they consumed a lot of stews and one-pot meals that were derivatives of the things that they ate when they were free people. So those were things like beans, stews made with beans, all kinds of beans. Particularly cow peas. You see a lot of these stews that also had yams. Yams were inexpensive but they were also the most important staples of many people who came from West and Central Africa.

A lot of those stews were made with oil, dende oil, which is also called palm oil. A lot of those stews and one-pot meals were made with palm oil, so they continued that. And also rice. Rice was one of those things that was incorporated in some of those dishes that were given to enslaved people.

Q: How did these diets shift under enslavement?

A: A lot of what they consumed were rations. And the most popular ration given out to enslaved people as an inexpensive staple was cornmeal. Corn is something that the Portuguese introduced to the people of West and Central Africa before they came here. So, it wasn’t the first time they used corn. A lot of those things just continued when they got here. There were also enslaved people who had small plots of land, where they would raise their own grains like corn.

And depending on where you were living, there were people who received fatback or the most fatty part of the pork or salt pork. That was a ration that was pretty consistent throughout the southern United States because it was inexpensive to raise hogs. And it was inexpensive to preserve that meat.

Then you also had the sweet potato begin to replace the yams. Even today, most African Americans couldn’t tell you the difference between a yam and a sweet potato, and they will substitute one for the other in dishes like candied yams, but they are really making candied sweet potatoes. But that was a staple.

Q: How did the enslaved Africans of the Caribbean and the U.S. fortify their diets?

A: This was an economic institution, so what was given to enslaved people as rations was the least expensive output. If you did not subsidize your diet with something you could have grown, you probably would have starved or close to starved. So that’s what they did. They had their own gardens where they would grow things—things like cow peas, lima beans black eyed peas, all kinds of legumes. They would raise their own animals—so poultry, chicken.

In Africa, people consumed largely a poultry in the form of a guinea hen. And chicken became the substitute for that when they came to America. There were still some places were people raised guinea hen, but people continued to consume chicken. It was inexpensive again to raise. And it was one of those things where they would produce it to consume or produce it for the one free day of the week, which was Sunday, to sell.

Now they did receive things like flour. But again, that was in a special occasion ration. Or you would have sold enough chicken or hogs to buy something like flour on a special occasion. So during the week, enslaved people ate things like ho cakes, cornbread or ashcakes (which is when you take the cornmeal and combine it with water and you cook that actual cake over ashes). And on Sundays, when people did have the day off, and if you had the resources and opportunity, you would bake biscuits or fry chicken. A lot of those things that were a part of our cuisine, they come out of survival techniques.